© Mark Hertzberg (2025)

There once was a Frank Lloyd Wright – designed building here, in the midst of the splendor of the Canadian Rockies, in Banff, Alberta.

There once was a Frank Lloyd Wright – designed building here, in the midst of the splendor of the Canadian Rockies, in Banff, Alberta.

Banff, Alberta does not immediately come to mind when people think of communities with buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. They are more likely to think of Bear Run, Buffalo, Los Angeles, New York, Racine, and, of course, Spring Green. However, Wright’s work crossed national boundaries, with commissions in Egypt, India, Iraq, Italy, Japan, and Mexico, as well as in Canada. Few of the international commissions were realized, but two in Canada were.

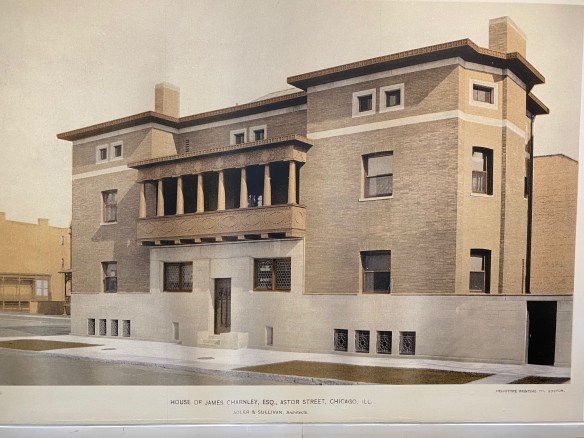

Similarly, when the name “Sullivan” comes to mind in discussions of Wright, people immediately think of Louis Sullivan, Wright’s ‘Leiber Meister.” But it was a different architect named Sullivan, Canadian architect Francis S. Sullivan, who also became part of Wright’s history, beginning in 1911.

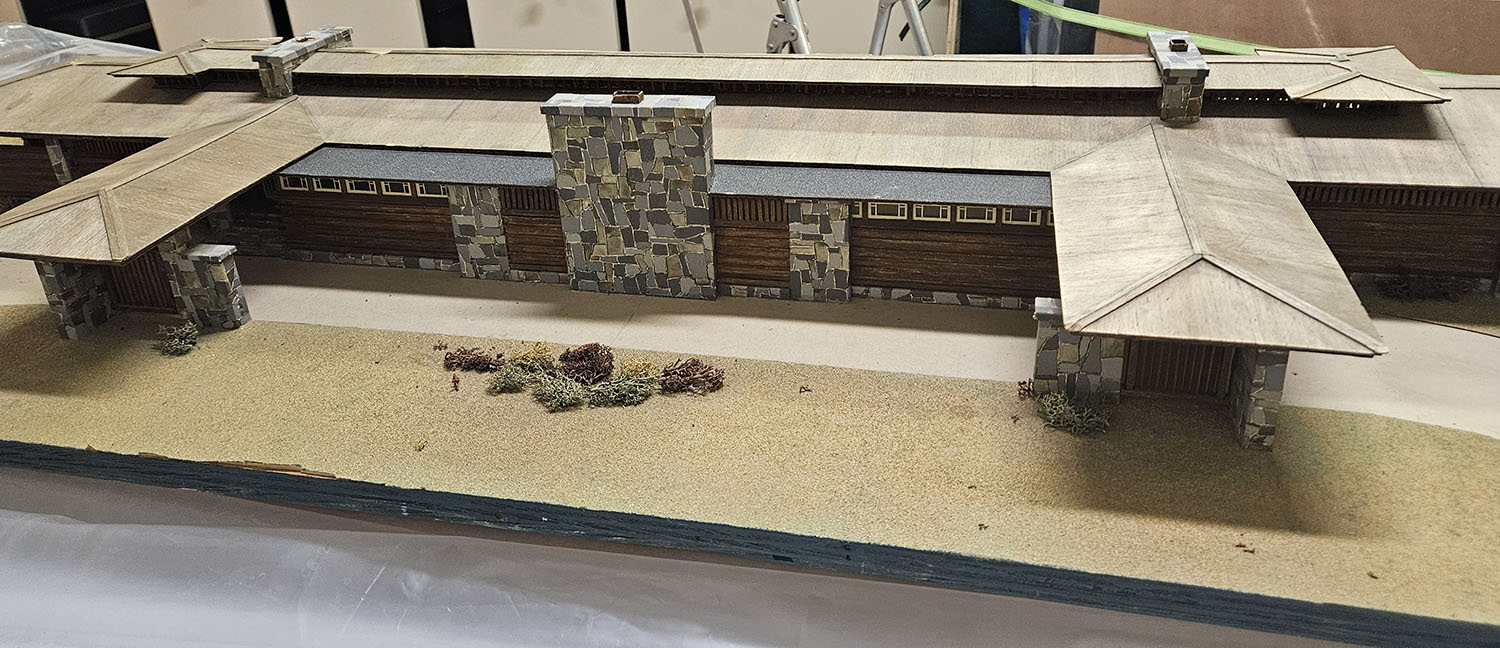

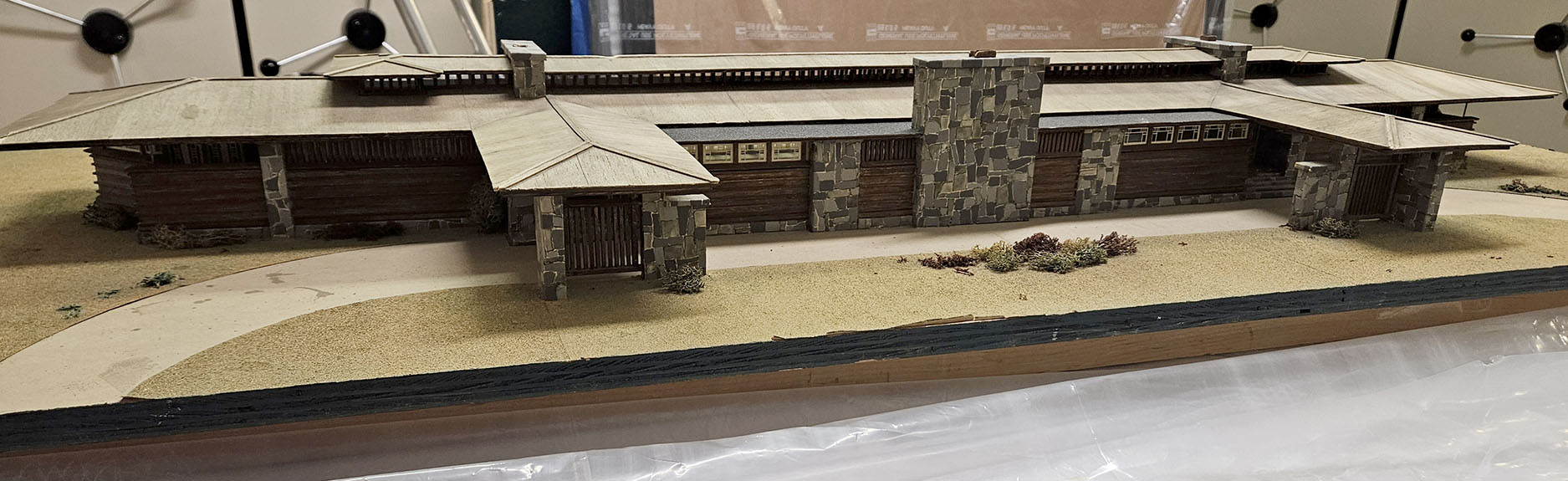

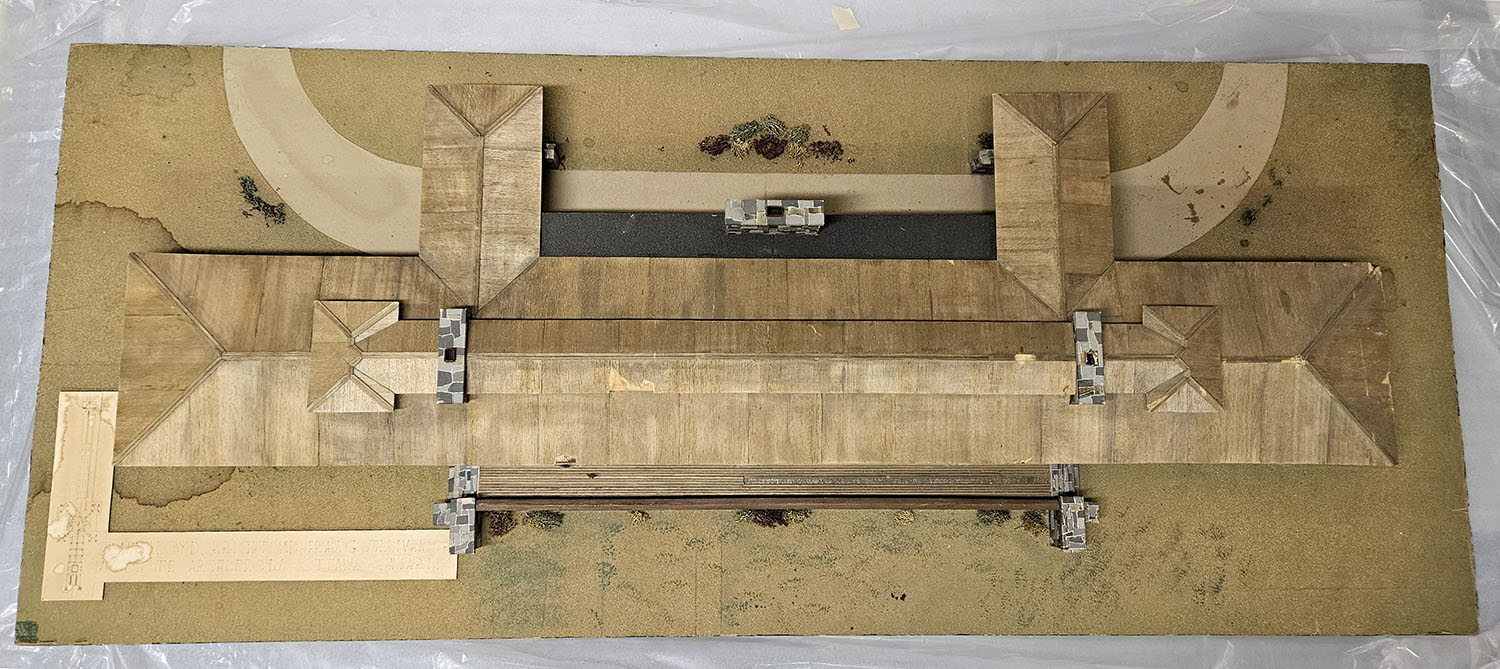

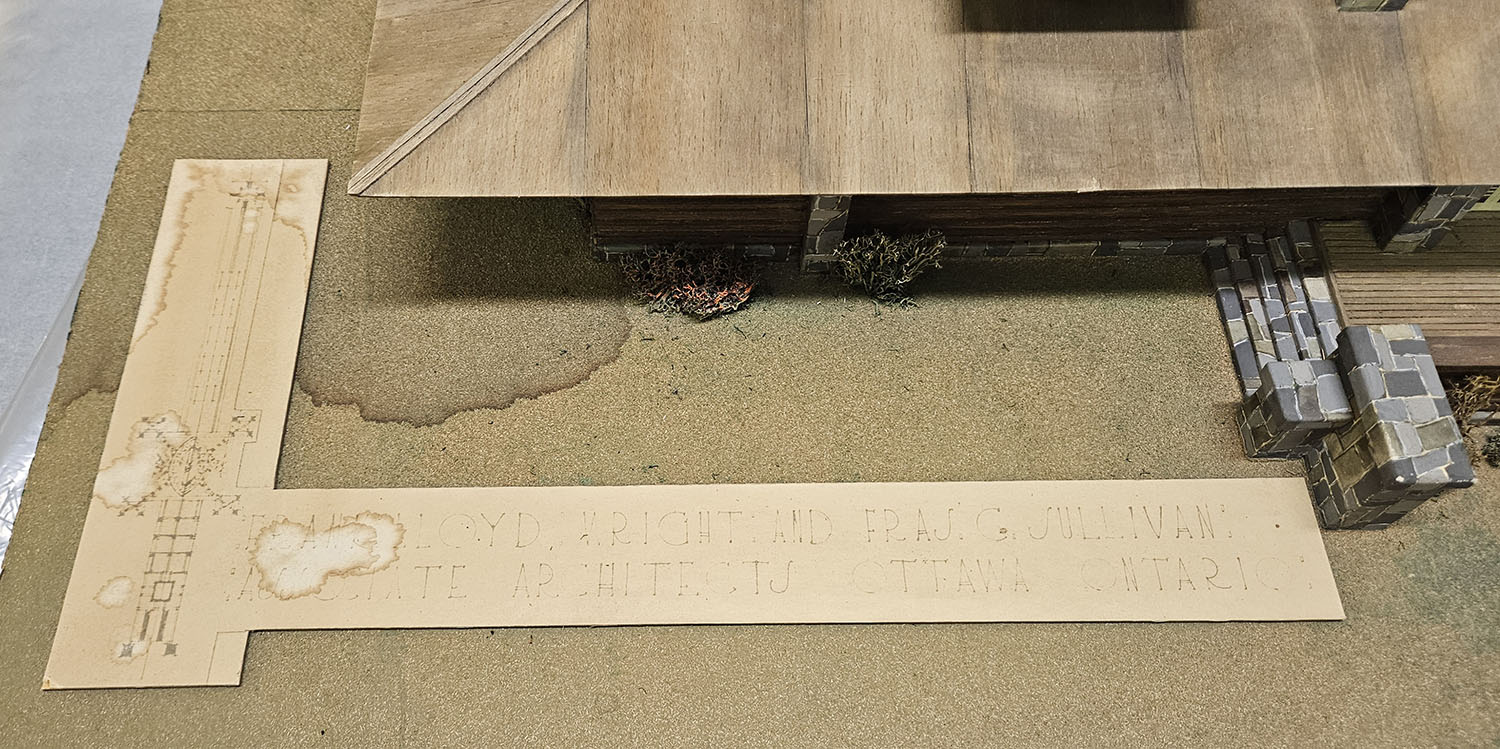

There were four Wright – Sullivan collaborations. The only one built was the Banff National Park Pavilion, about 70 miles west of Calgary. Designed in 1911, it was completed in 1913, and demolished in 1938. The legend on a model of it in the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies archives in Banff credits the building to “Frank Lloyd Wright and Francis C. Sullivan Associates Architects Ottawa Ontario.”

Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion West Face – Image #V683/VI/A/PG-336 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections

Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion West Face – Image #V683/VI/A/PG-336 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections

From the University of Calgary Digital Collection

From the University of Calgary Digital Collection

Their three unrealized projects were a railroad station for Banff (1913), the Pembroke Carnegie Public Library in Pembroke, Ottawa, Ontario (1913), and, according to Wright scholar Douglas Steiner, a “Ladies Kiosk” in Ottawa (1914). Wright’s other realized commission in Canada was the E.H. Pitkin Residence on Sapper Island, Desbarats, Ontario (1900).

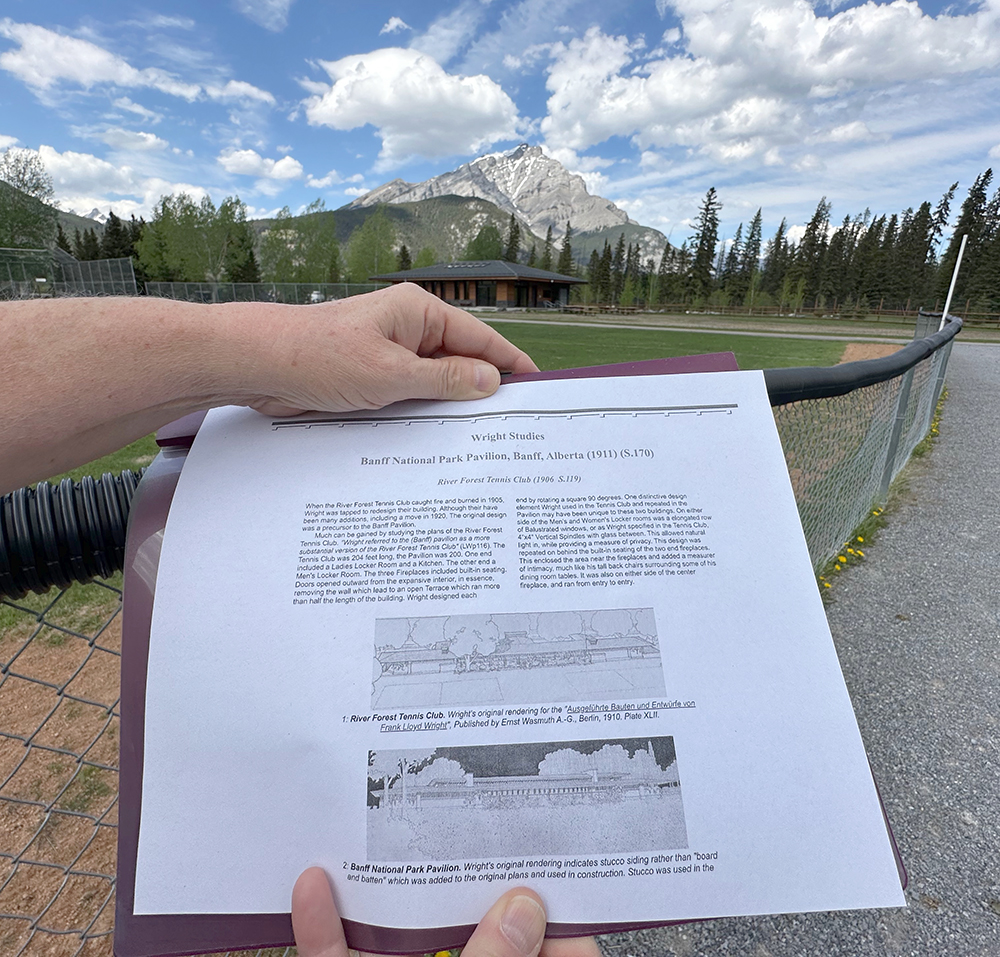

Steiner documented the history of the Pavilion, and related structures in 2010 on his http://www.steinerag[Steiner Agency].com website. Much of the information below was gleaned from his article:

http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact Pages/PhRtS170.htm#Site

Wright was usually fastidious in his oversight of where his designs would be built. Either he was not, in this instance, or else it is possible that his client, the Canadian Department of Public Works, had the final say.

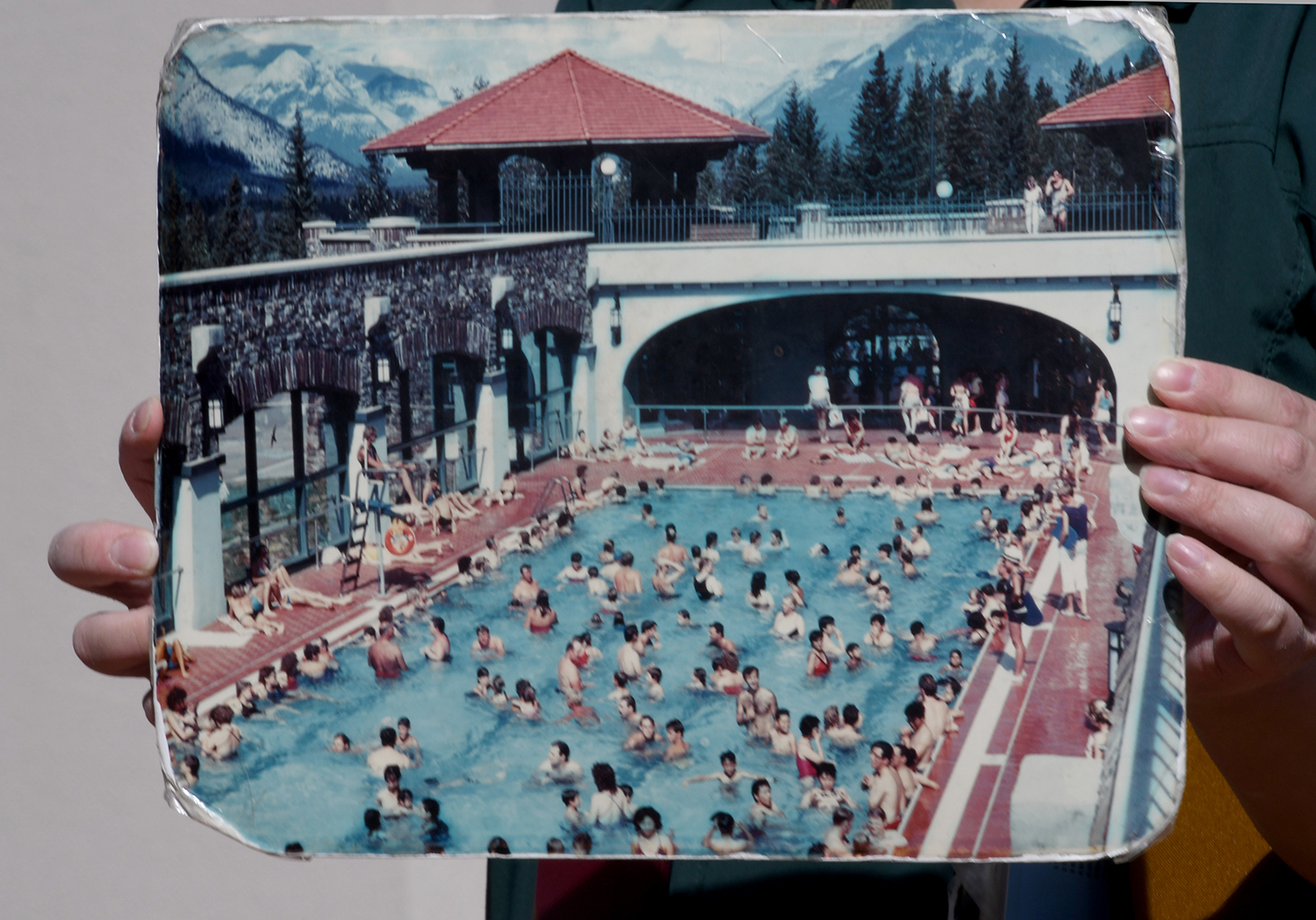

Banff National Park was Canada’s first national park. The town became a tourist destination in 1883 after three men working on the transcontinental railroad discovered hot sulphur springs. The springs, pools, and their outbuildings are now a tourist destination known as the Cave and Basin, although there is no more bathing at the site.

The Pavilion was sited in what are called the Recreation Grounds, near the Bow River, south of downtown Banff. It was controversial from the start. The consensus among residents seemed to be that the Pavilion should be suited to year-round use and reflect their interest in sports such as curling and ice hockey. The government and Wright thought otherwise. The Wright / Sullivan design was best suited for use in warm weather. The exterior and floor plan were similar to Wright’s River Forest (Illinois) Tennis Club (1906), below:

The River Forest Tennis Club in 2020

The River Forest Tennis Club in 2020

According to the Banff Crag and Canyon newspaper, “The structure will be of rustic frame, one story in height, with cement and rubble foundation. The outside dimension will be 50 x 200 feet. The interior will contain a general assembly or lounging room 50 x 100 feet, with a ladies’ sitting room 25 x 50 feet at one end and a sitting room for gentlemen, 25 x 50, at the other end. Dressing rooms, lockers, etc., and provided for also three cobblestone fireplaces. Inside had three fireplaces, a men’s smoking room, a women’s lounge, and a common area between them.”

Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion Interior Image # V683/441/na66/1471 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections

Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion Interior Image # V683/441/na66/1471 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections

The Pavilion served as Quarter Master’s Stores during World War I. If the design was problematic, at least for the residents, the site of the Pavilion near the Bow River was more problematic, ultimately fatally so for the structure. The river could get very angry. It did so particularly in 1920 and 1933 when it flooded around the Pavilion, doing irreparable damage to it, and ultimately dooming it. The newspaper wrote of the 1920 flood, “The grounds in front of the recreation building were under water last week, and it was possible for a man, if so inclined. to wade out to the building, sit on the steps and fish.”

From the University of Calgary Digital Collection

From the University of Calgary Digital Collection

The wrecking ball finally came in 1938, just a quarter century after it opened. A 2016 proposal by Michael Minor, an American, to raise money for the Pavilion to be reconstructed did not materialize.

My wife and I were visiting Banff this spring and were anxious to find the Pavilion’s site. That was a challenge because there is no historic marker. We took hints from Steiner’s article. Patricia Thomson, our Canadian Rockies tour guide, graciously took time on a free afternoon to help us wander the area near the Bow River Bridge, Cave Avenue, and Sundance Road, near the Recreation Grounds. She had already gotten some leads from her brother, who works for the provincial parks department. Most significantly, he directed us to Steiner’s article.

Patricia Thomson helps us locate the site of the Pavilion. Photo by Cindy Hertzberg

Patricia Thomson helps us locate the site of the Pavilion. Photo by Cindy Hertzberg

Reconstruction of the building in an area that has new recreation amenities is not likely to happen, but Banff’s Heritage Committee, which considered Minor’s reconstruction proposal, had discussed the idea of a “Landmarks and Legends” marker at the site before the Pandemic. We are past the Pandemic. Now is the time to reconsider the idea of signage.

Until such signage were to come to fruition, the only tangible evidence of the Banff National Park Pavilion in Banff is a model in the basement archives of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

Images courtesy of The Whyte

Images courtesy of The Whyte

Postscript: According to “In Wright’s Shadow” (published by the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation in 1998), Sullivan worked in Wright’s Oak Park studio in 1907 and 1908 before returning to Canada. He worked with Wright in Arizona in 1916 on drawings for the Imperial Hotel. He did not accept Wright’s offer for him to work with him in Japan on the hotel. Sullivan died of throat cancer in 1929, living as a guest of Wright’s at Ocatilla, his Arizona desert camp.

Thank you to Randolph C. Henning and Keiran Murphy for their assistance with this piece.

Please scroll down for previous articles on this Wright blog.

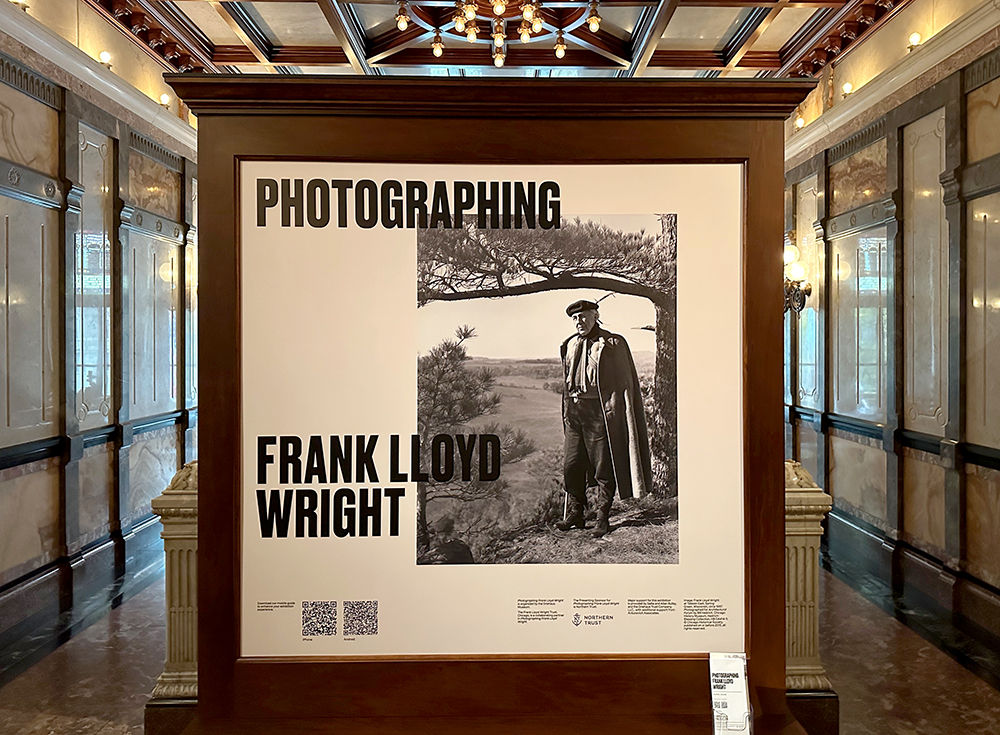

“Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright” is not just another exhibit of Wright’s designs and the stories behind them. Although the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation published “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fifty Views of Japan” in 1996, it may not be well known that Wright was an avid photographer early in his career. He had a darkroom at his Home and Studio.

“Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright” is not just another exhibit of Wright’s designs and the stories behind them. Although the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation published “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fifty Views of Japan” in 1996, it may not be well known that Wright was an avid photographer early in his career. He had a darkroom at his Home and Studio.

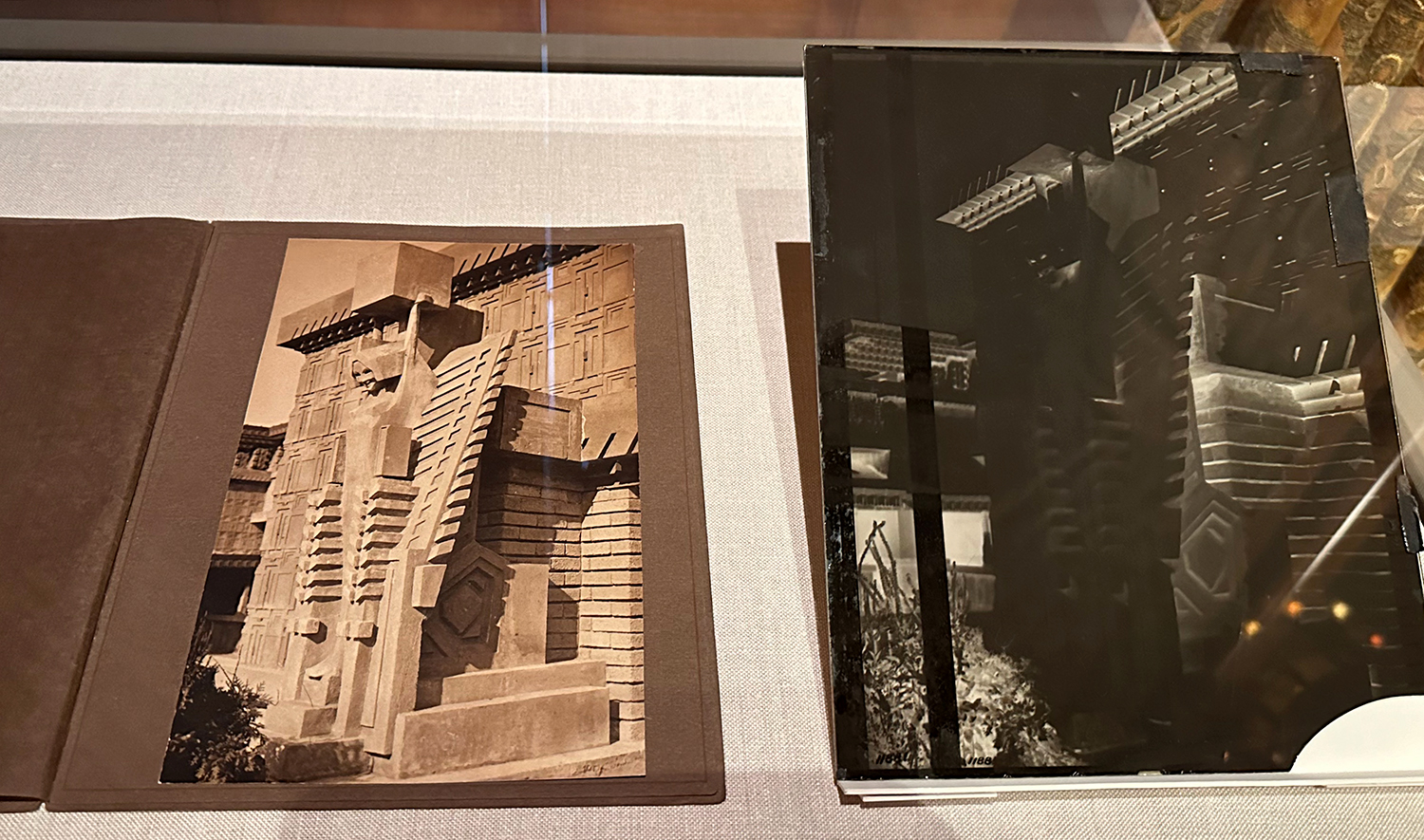

The print and negative of a Fuermann photo of Midway Gardens

The print and negative of a Fuermann photo of Midway Gardens