Text and photos © Mark Hertzberg (2024)

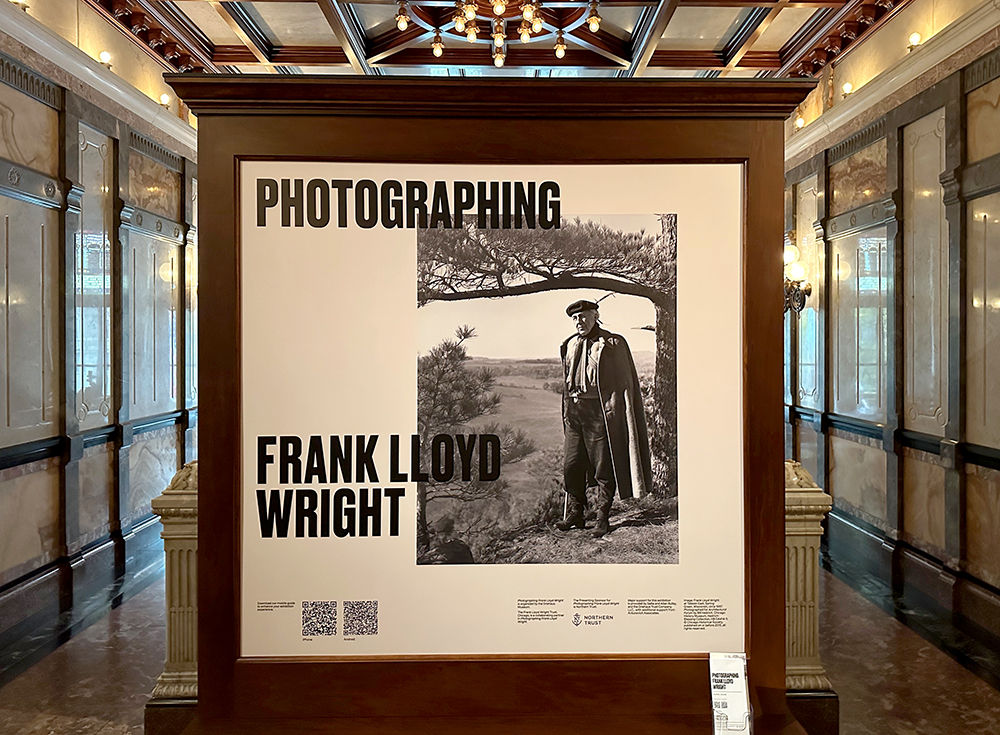

A new exhibit related to Frank Lloyd Wright opened two weeks ago at the Driehaus Museum in Chicago. The museum is in the former Gilded Age Nickerson Mansion (1883) on Chicago’s Near North Side, at 50 East Erie Street.

“Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright” is not just another exhibit of Wright’s designs and the stories behind them. Although the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation published “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fifty Views of Japan” in 1996, it may not be well known that Wright was an avid photographer early in his career. He had a darkroom at his Home and Studio.

“Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright” is not just another exhibit of Wright’s designs and the stories behind them. Although the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation published “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fifty Views of Japan” in 1996, it may not be well known that Wright was an avid photographer early in his career. He had a darkroom at his Home and Studio.

The exhibit features some of his photography, including self portraits, photographs of Hillside Home School, photos of the Home and Studio, and some of the photographs he took in Japan in 1905. There is even one he took of his first wife, Catherine Tobin Wright, reading to one of their sons. The balance of the exhibit on the museum’s second and third floors shows how a variety of noted photographers of his work interpreted his buildings. The photographers featured are Henry Fuermann & Sons, Hedrich-Blessing, Pedro Guerrero, Torkel Korling, Julius Shulman, Ezra Stoller, and Edmund Teske. Fuermann’s 4×5 camera is shown above.

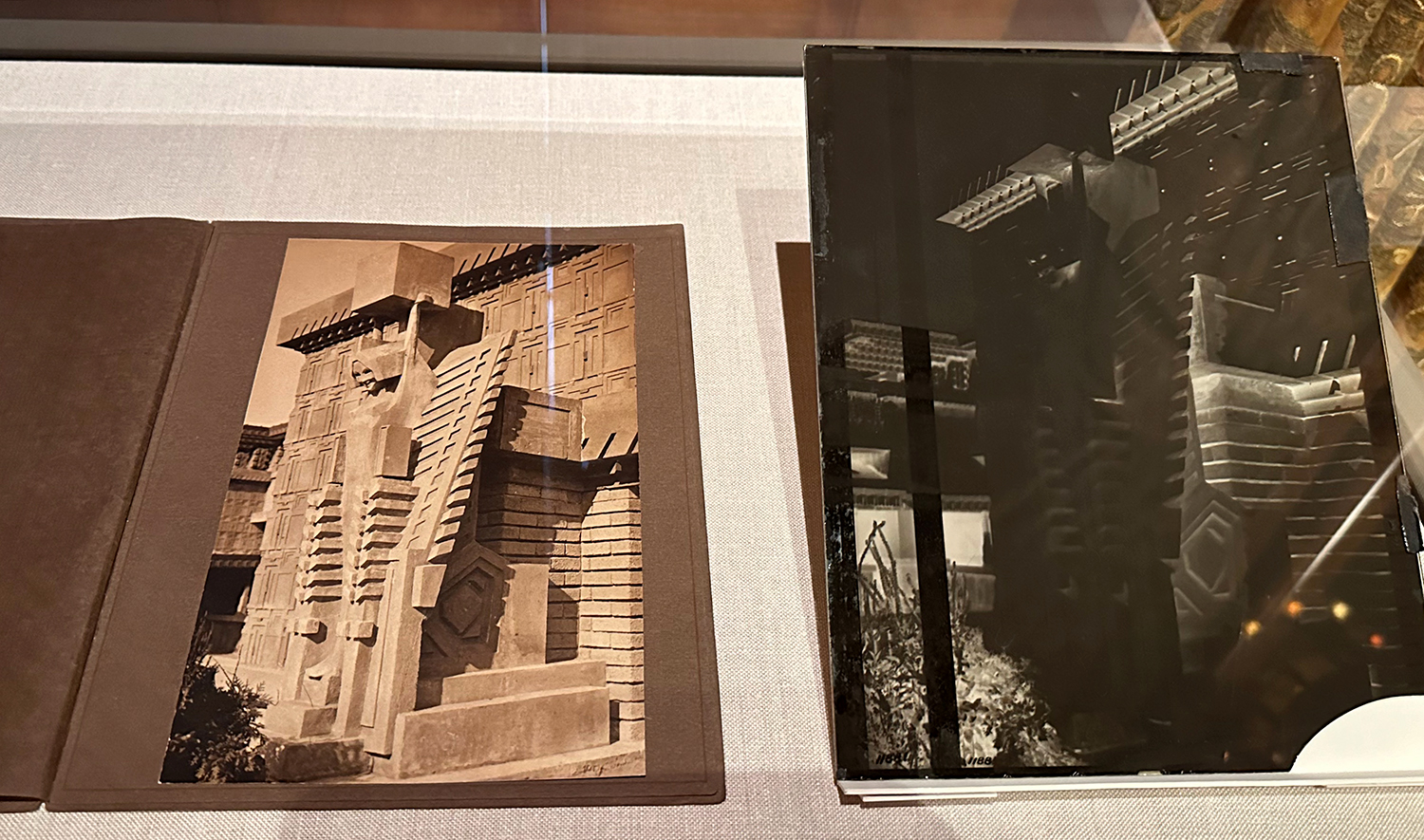

Put out of your mind the ease of taking pictures today, and take another look at Fuermann’s camera. It used single sheets of film which had to be taken out of the camera after each photograph was taken (unlike my cameras which can take 10 frames a second). Each photograph would be carefully composed. There was no “chimping” (the term photojournalists use to describe their colleagues who quickly look at the screen on the back of the camera to see if they got the image they wanted), each sheet of film had to be developed in the darkroom. The image was reversed on a negative. Photographers get adept at “reading” negatives, but only after making a print did the photographer know for certain if the exposure was correct, and the composition perfect.

The print and negative of a Fuermann photo of Midway Gardens

The print and negative of a Fuermann photo of Midway Gardens

The timeline of the photographs covers Wright’s career, from photos of students at the first Hillside Home School for his aunts, through to the Guggenheim Museum. A number of the exhibit pieces are from Eric O’Malley’s extraordinary collection, and are shown courtesy of the OA+D (Organic Architecture and Design) archives.

When people ask me what attracts me to Wright’s work I reply that it is the breadth of it, so one of my favorite parts of the exhibit was in the section devoted to Pedro Guerrero’s work. On the left in the photo below we see the Robert Llewellyn House (1953) in Bethesda, Maryland, and upper right is the Rose Pauson House (1940) near Phoenix. Look at these two photographs taken from the same vantage point (below the house, looking up) and look at how the same photographer recorded the same architect’s different interpretations of a client’s needs a decade apart (the third photo is Guerrero’s photo of the David and Gladys Wright House near Phoenix, 1950). Wright’s vocabulary has changed dramatically, to respond to the program on his drawing board.

The only negative aspect of the exhibit is that I was surprised to find four significant errors in the text panels accompanying the photographs, this two weeks after it opened. The staff responded graciously when I mentioned the errors, and I expect that they will be corrected.

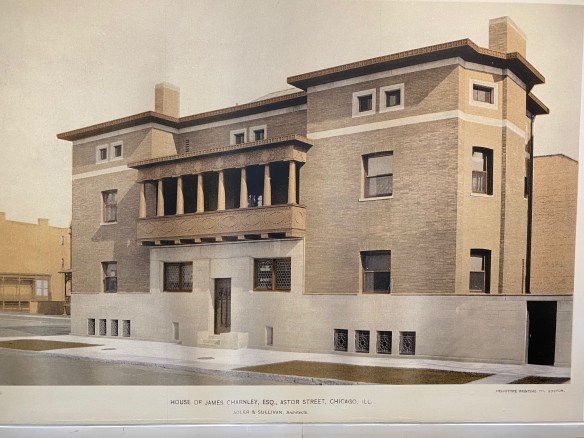

The exhibit runs through January 5, 2025. While any visit to the Driehaus is worthwhile, this one makes it even more so. Two years ago the museum had a wonderful exhibit dedicated to Richard Nickel and Louis Sullivan. The late Richard H. Driehaus, who restored the Nickerson Mansion, is well known to readers of the National Trust for Historic Preservation magazine, Preservation. Admission is free to visitors who have North American Museum Reciprocity passes.

Links:

Driehaus Museum:

https://driehausmuseum.org/exhibition/photographing-frank-lloyd-wright

OA+D:

Frank Lloyd Wright Trust:

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation:

National Trust for Historic Preservation:

Please scroll down for earlier posts on this site