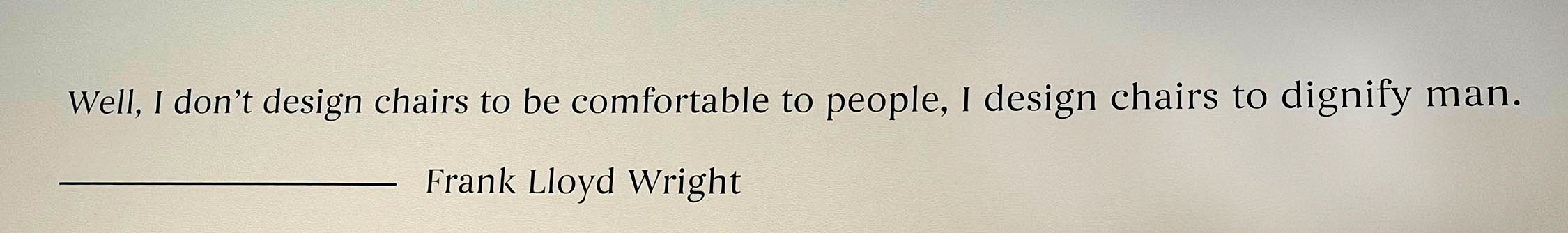

A quick test: think “Frank Lloyd Wright.” Chances are that images of Fallingwater, the Robie House, the SC Johnson Administration Building or other structures came to mind. It is a safe bet that you did not visualize any of his furniture. It has oft been written that Wright was concerned about the whole of his commissions…designing furnishings (and sometimes even clothing) for his clients, rather than only their home or public building. Yet, relatively scant attention has focused on his furniture en toto.

The four pieces at the entry to the show below the quotation from Wright are, from left to right: Easy Chair for Francis W. Little House, Peoria, c. 1903; Musician’s Chair for the Dana-Thomas House, Springfield, c. 1903-1904; Slant Back Chair for the Hillside Home School, Spring Green, c. 1902-1903; and Side Chair for the Avery Coonley Playhouse, Riverside, c. 1912.

There have been only three research-based books on the subject – three out of how many hundred books about Wright? That was the impetus for the “Frank Lloyd Wright- Modern Chair Design” exhibition at the Museum of Wisconsin art (MOWA) in West Bend, Wisconsin. The exhibit ran from October – January.

Thomas Szolwinski, MOWA’s Curator of Architecture and Design told guests during a curated tour in January that Wright designed more than 800 pieces of furniture. Some clients elected not to have the furniture built, and some pieces no longer exist. Wright designed “different chairs for different purposes,” noted co-curator Eric Vogel. “Wright was dismissive of his furniture,” and “Wasmuth was not interested in his interiors” for the famous portfolio.

Vogel has examined every one of the Wright furniture drawings. Vogel and Szowinski selected 42 pieces to exhibit. Thirty were located and lent to MOWA. The other dozen were built for the exhibition, meticulously following Wright’s drawings by Current Projects, by Wright’s great grandson S. Lloyd Natof, and by Stafford Norris III, whose mother and step-father are stewards of Wright’s Malcolm and Nancy Willey House in Minneapolis. They used the drawings to make computer models before making wood models of the pieces. The upholsterer was Chad Alexander Matha. The spun aluminum pieces designed for the Guggenheim Museum were fabricated by Butler Metal Spinning Corp.

The dining room set from the Malcolm and Nancy Willey House in Minneapolis

The dining room set from the Malcolm and Nancy Willey House in Minneapolis

Above: Dining Chair for the Emil Bach House, Chicago, c. 1913

Right: Armchair for Taliesin, Spring Green, designed c. 1929, and second from right, and below, “Mori” Chair for the S. Mori OrientalArt Studio and Japanese Print Shop, Chicago, designed c. 1914

Above and below: Armchair for Taliesin, designed c. 1914; fabricated 2025 by Stafford Norris III

Szolwinski noted how details of the chair echoed the windows at left.

Above: Armchair for Taliesin, designed 1914

Above: Armchair for the Francis Little House II, “Northome,” Wayzata, Minnesota, designed c. 1913; fabricated 1970

Chair for the A. D. German Warehouse, Richland Center, Wisconsin, designed c. 1935; fabricated 2025 by Current Projects

Above, Ten pieces make up the famous “Origami” Armchair for Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona, designed 1946

Honeycomb Lounge Chair, Prototype for Heritage–Henredon, Henredon Furniture Co., Morganton, North Carolina, designed c. 1955

Again, furniture echoes the design of the house…here are hassocks for the Robert Llewellyn Wright House, Bethesda, Maryland, designed c. 1957–58

Café Chairs and table for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, designed c. 1957; fabricated 2025 by Butler Metal Spinning Corp.

The museum partnered with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation to develop the exhibition. The 30 extant pieces were lent by 15 institutions and homeowners, integrating Wright’s furniture with his architecture. Szolwinski said there were three obstacles faced by the curators, “Time, money, and space.” The fabricators of the new pieces were sometimes challenged by ambiguities in the drawings. Using Taliesin as “a lens to see what [Wright] did” the curators looked for lesser known designs, eschewing, for example, the well known pieces designed for the Larkin Building and the SC Johnson Administration Building. Wright designed more flexible furniture beginning in the 1930s, as his house designs became smaller with the leap from Prairie-style to the Usonian designs. This was also some of the earliest use of construction plywood, “It was thin, but strong, and affordable.”

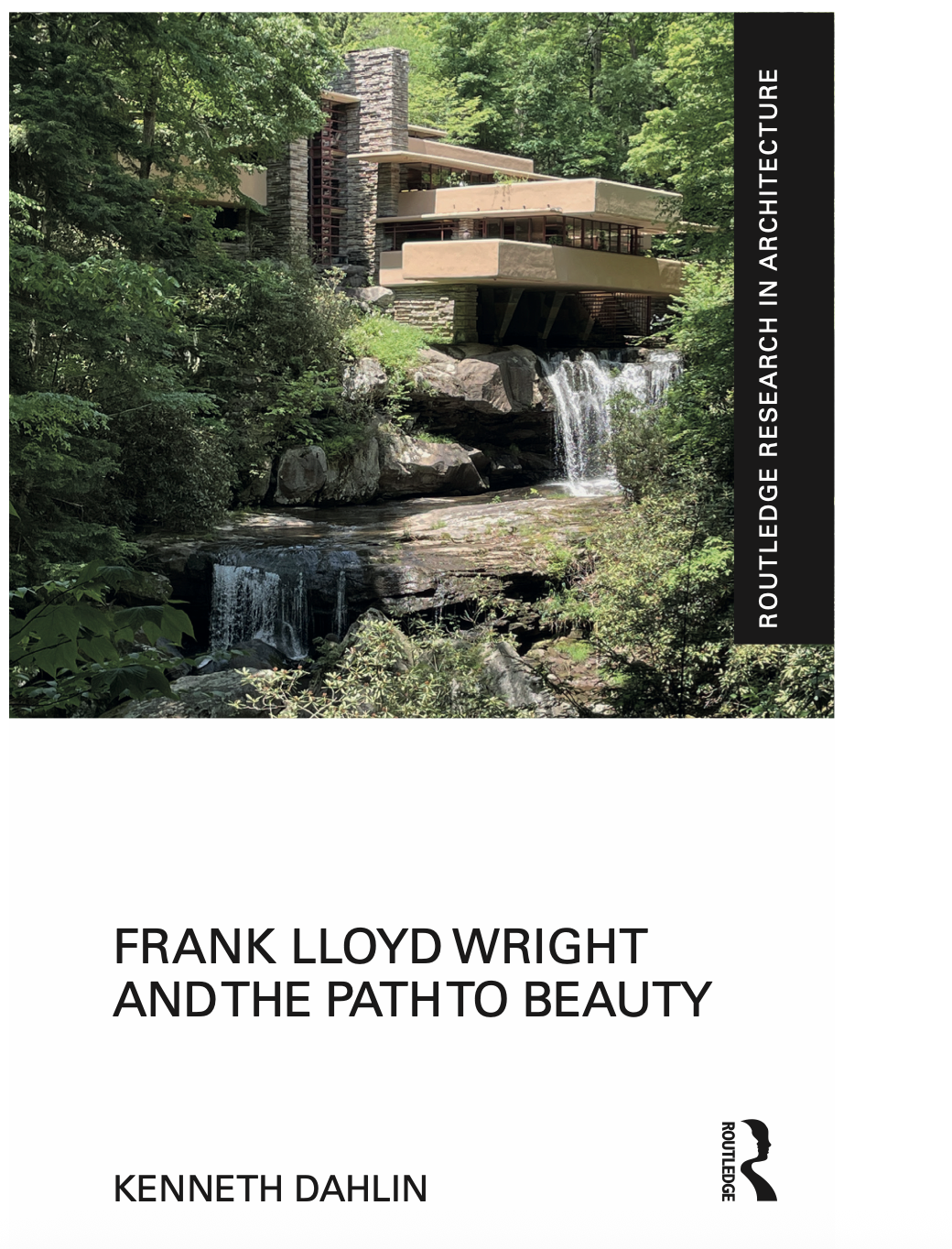

Further reading: I have presented only an overview of this important exhibition. I highly recommend the exhibition book published by MOWA. It is written by Szolwinski and Vogel, with the assistance of Jennifer Gray of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. She is Vice President of the Foundation and Director of the Taliesin Institute:

https://wisconsinart.org/product/frank-lloyd-wright-modern-chair-design/

MOWA (Museum of Wisconsin Art): https://wisconsinart.org

The Winter 2025 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly is devoted to “The Evolution of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Furniture: and has four important articles. The Quarterly is available only to members of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Follow this link to join: https://franklloydwright.org

Please scroll down for earlier posts on this website.

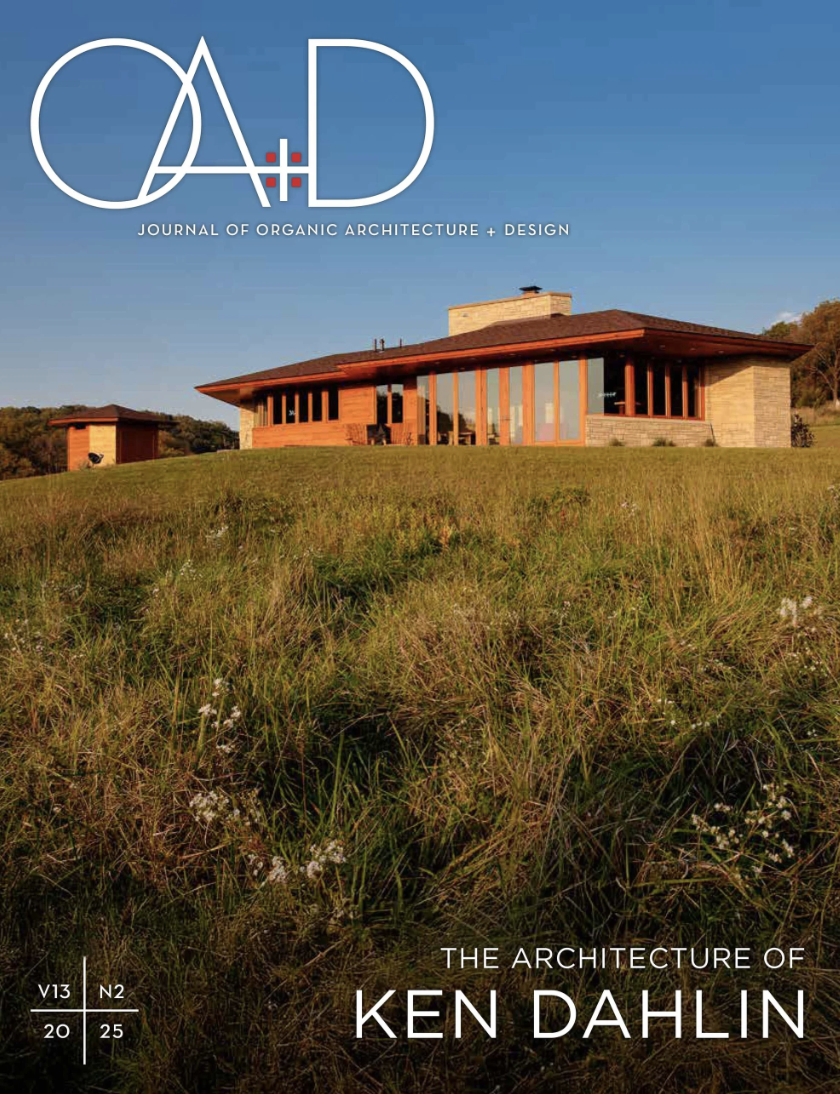

Ken Dahlin of Genesis Architecture photographs the house.

Ken Dahlin of Genesis Architecture photographs the house.

Barbara Gordon, Jeffrey Herr, and Scott Perkins present the Wright Spirit Award to Philip Palumbo, on behalf of his parents.

Barbara Gordon, Jeffrey Herr, and Scott Perkins present the Wright Spirit Award to Philip Palumbo, on behalf of his parents.

This photograph shows one of the two single family homes (the Model B1) and the four duplexes. The Model C3 single family home, below, sits to the right of the B1.

This photograph shows one of the two single family homes (the Model B1) and the four duplexes. The Model C3 single family home, below, sits to the right of the B1. Docent Bill Schumacher leads a tour of the Burnham Block, including the C3

Docent Bill Schumacher leads a tour of the Burnham Block, including the C3

Wright in Wisconsin board members discuss their purchase of the B1 in April 2005. Mike Lilek, the driving force behind the Burnham projects, is left. Barbara Meyer Elsner is third from right.

Wright in Wisconsin board members discuss their purchase of the B1 in April 2005. Mike Lilek, the driving force behind the Burnham projects, is left. Barbara Meyer Elsner is third from right.

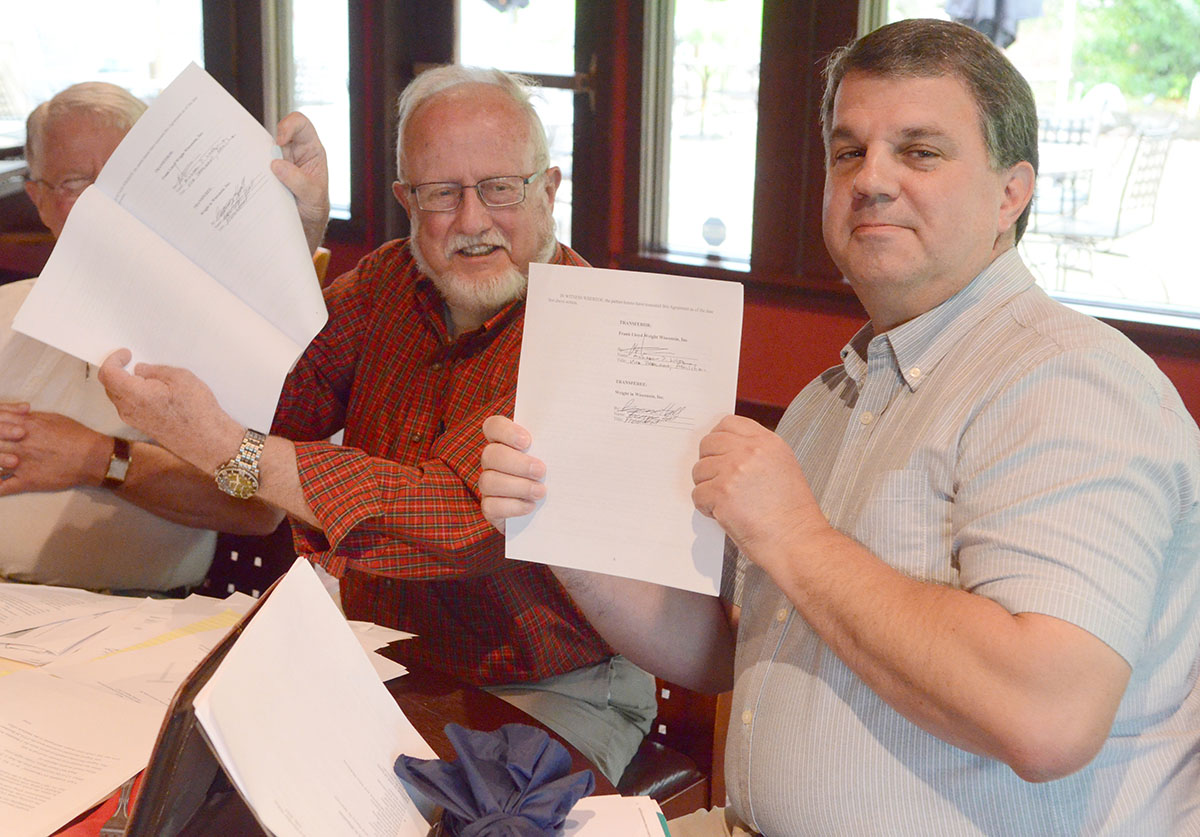

George Hall, left, and Mike Lilek sign the reorganization papers August 3, 2017.

George Hall, left, and Mike Lilek sign the reorganization papers August 3, 2017.

Andrew had 18 photo guests arriving shortly after 7 a.m. to photograph Frank Lloyd Wright’s Thomas P. Hardy house inside and out, top to bottom. Andrew had asked me a year ago to tell the photographers about Hardy and about the house. Tom Szymczak, the steward of the house, had two kringle and a pot of hot coffee waiting. I got there at 6:48 a.m. Before I could get the goodies out and turn on the lights, I had to take my own photos of the house at sunrise. So, first my photos, and then my photos of the photographers.

Andrew had 18 photo guests arriving shortly after 7 a.m. to photograph Frank Lloyd Wright’s Thomas P. Hardy house inside and out, top to bottom. Andrew had asked me a year ago to tell the photographers about Hardy and about the house. Tom Szymczak, the steward of the house, had two kringle and a pot of hot coffee waiting. I got there at 6:48 a.m. Before I could get the goodies out and turn on the lights, I had to take my own photos of the house at sunrise. So, first my photos, and then my photos of the photographers.

Hansen at her book talk at Boswell Books in Milwaukee, June 9, 2023.

Hansen at her book talk at Boswell Books in Milwaukee, June 9, 2023.

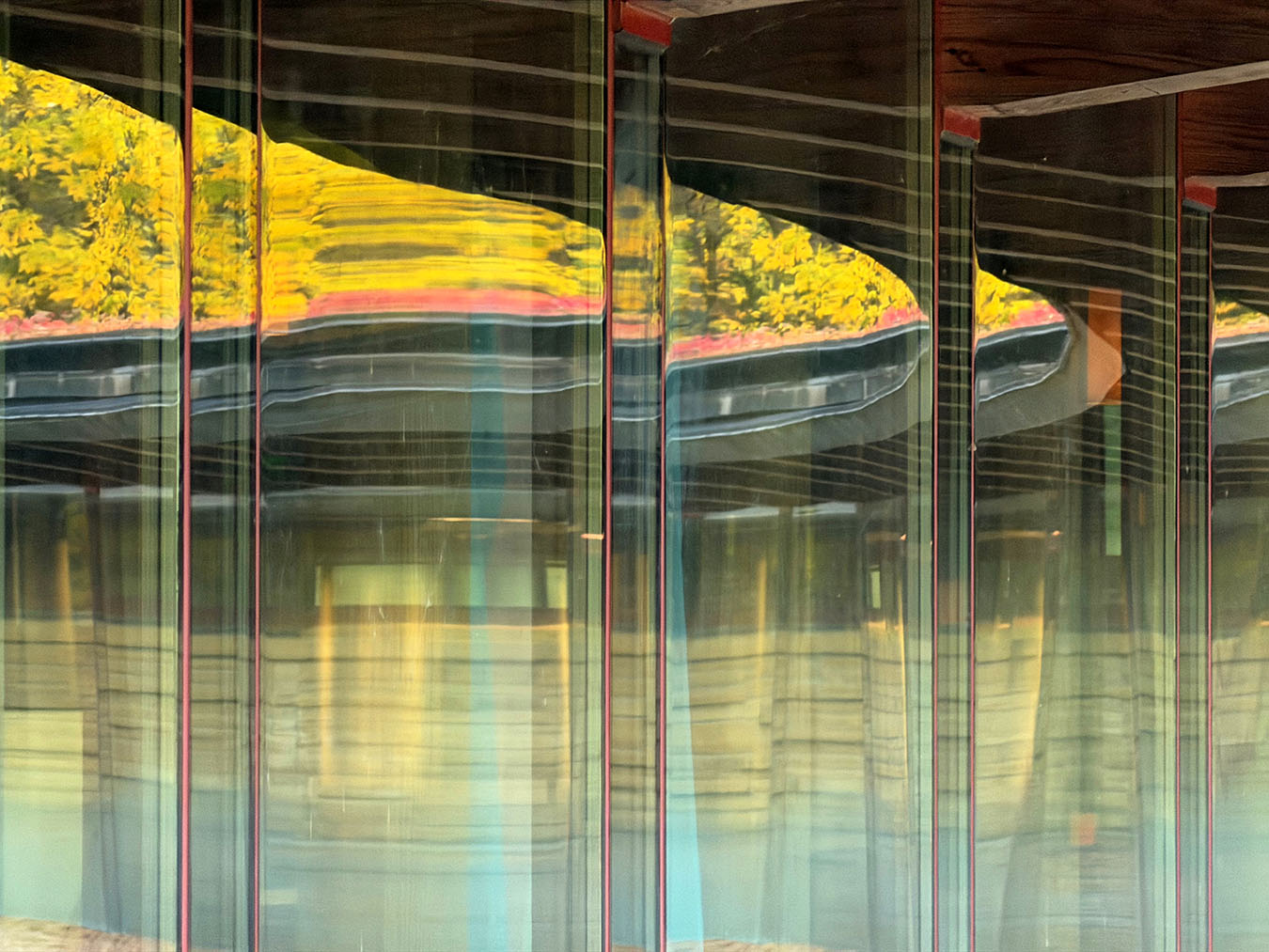

One of the entry way hallway windows is reflected in the two story living room windows that overlook Lake Michigan.

One of the entry way hallway windows is reflected in the two story living room windows that overlook Lake Michigan.

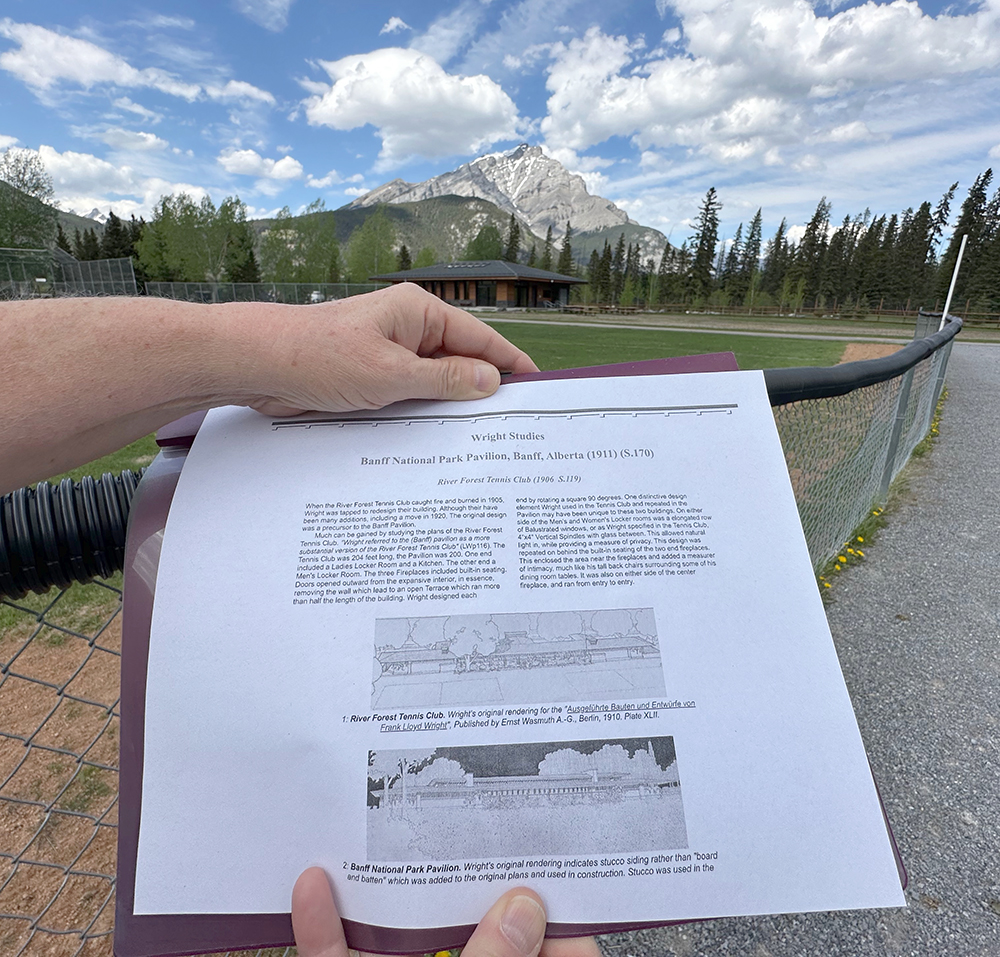

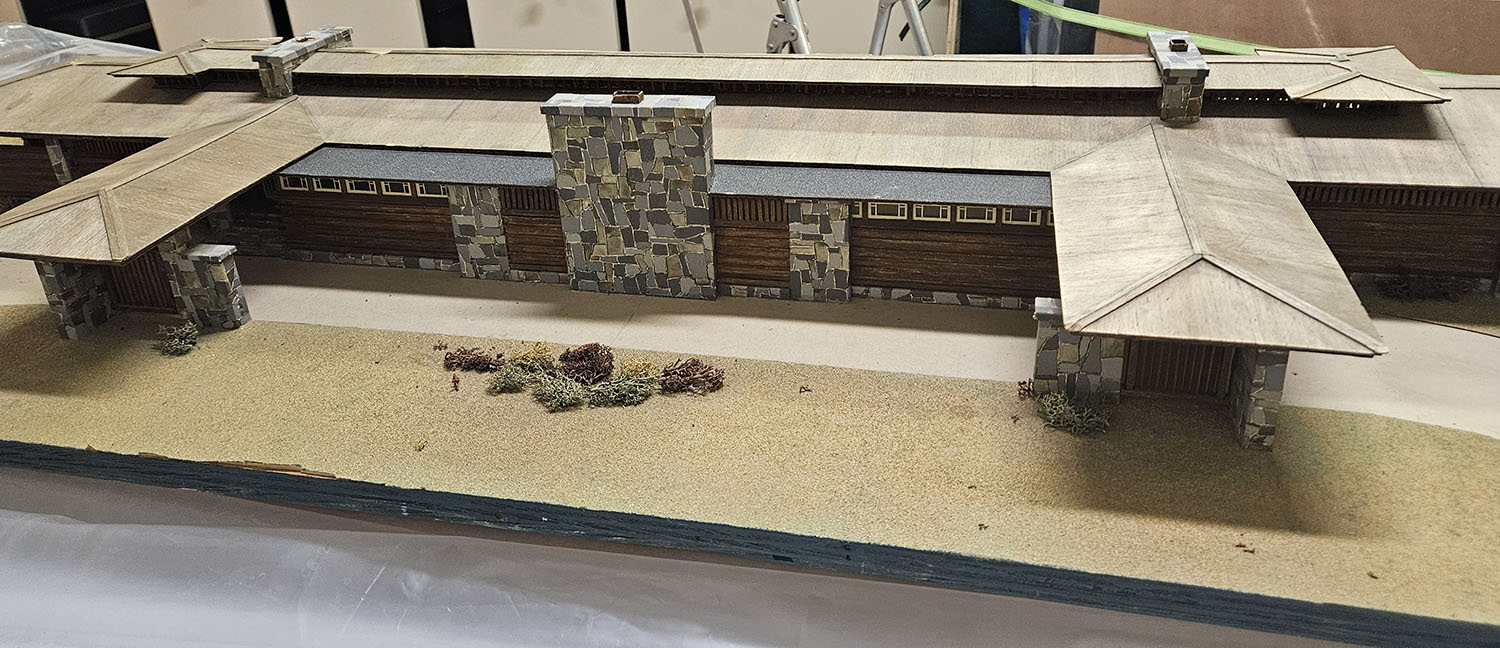

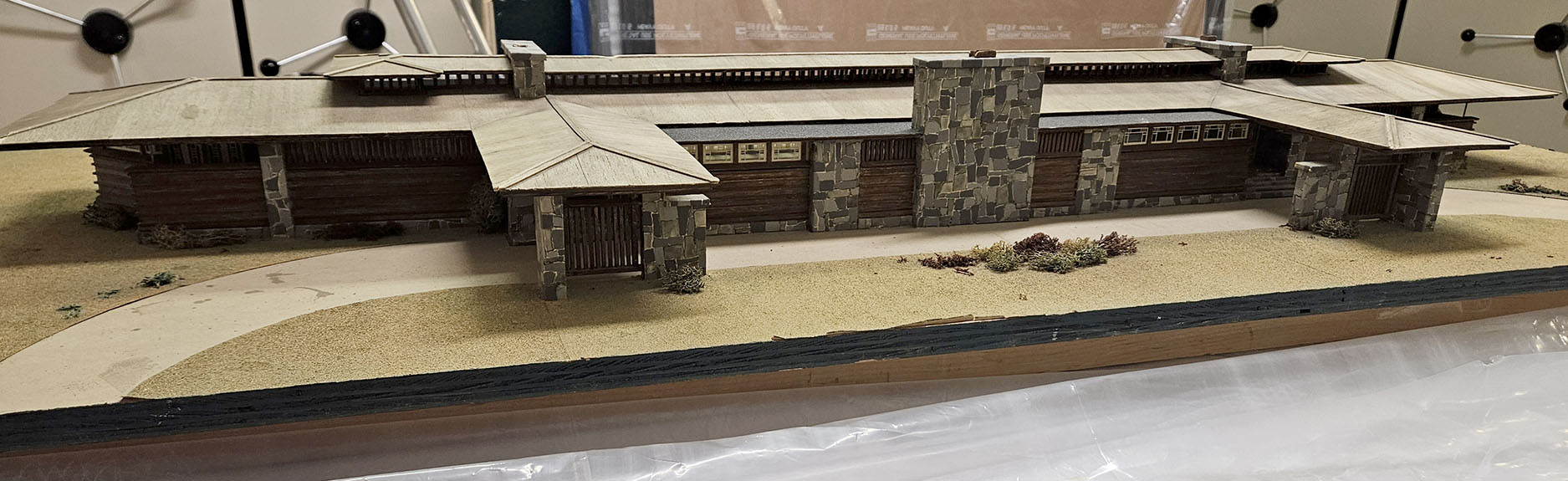

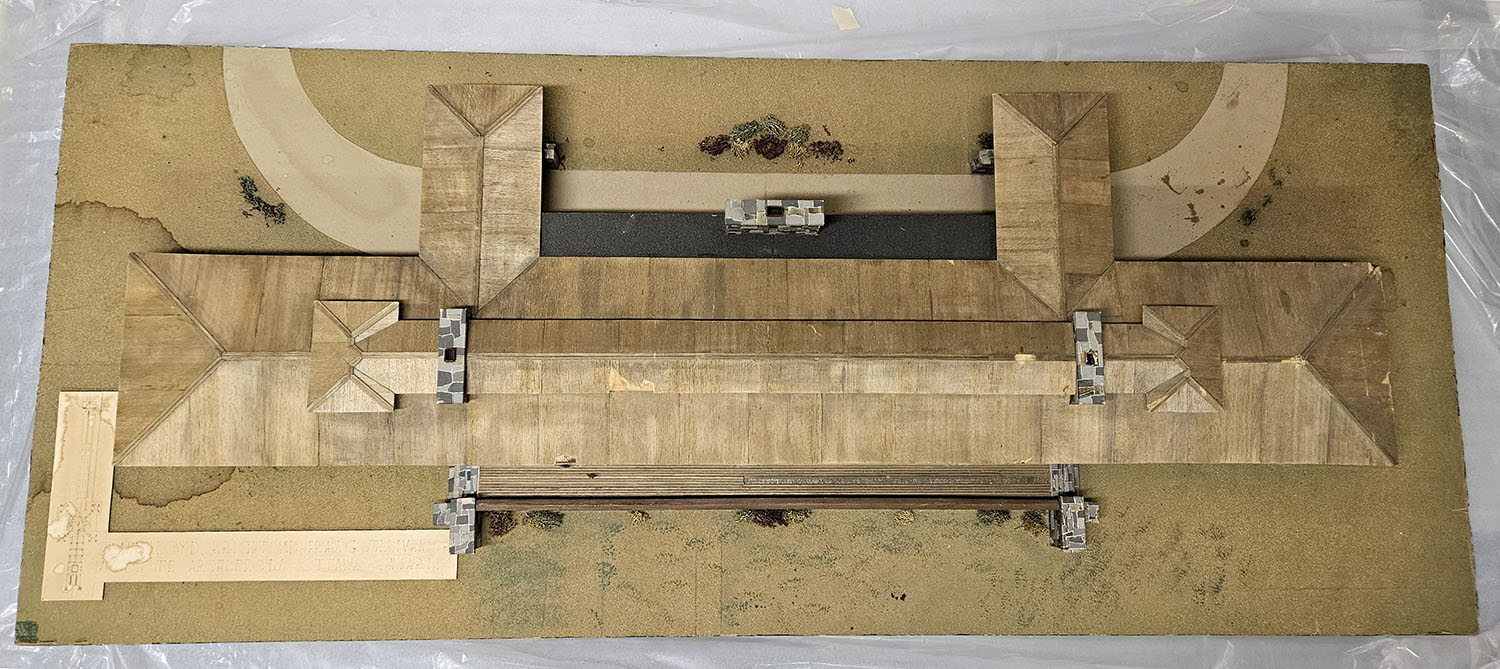

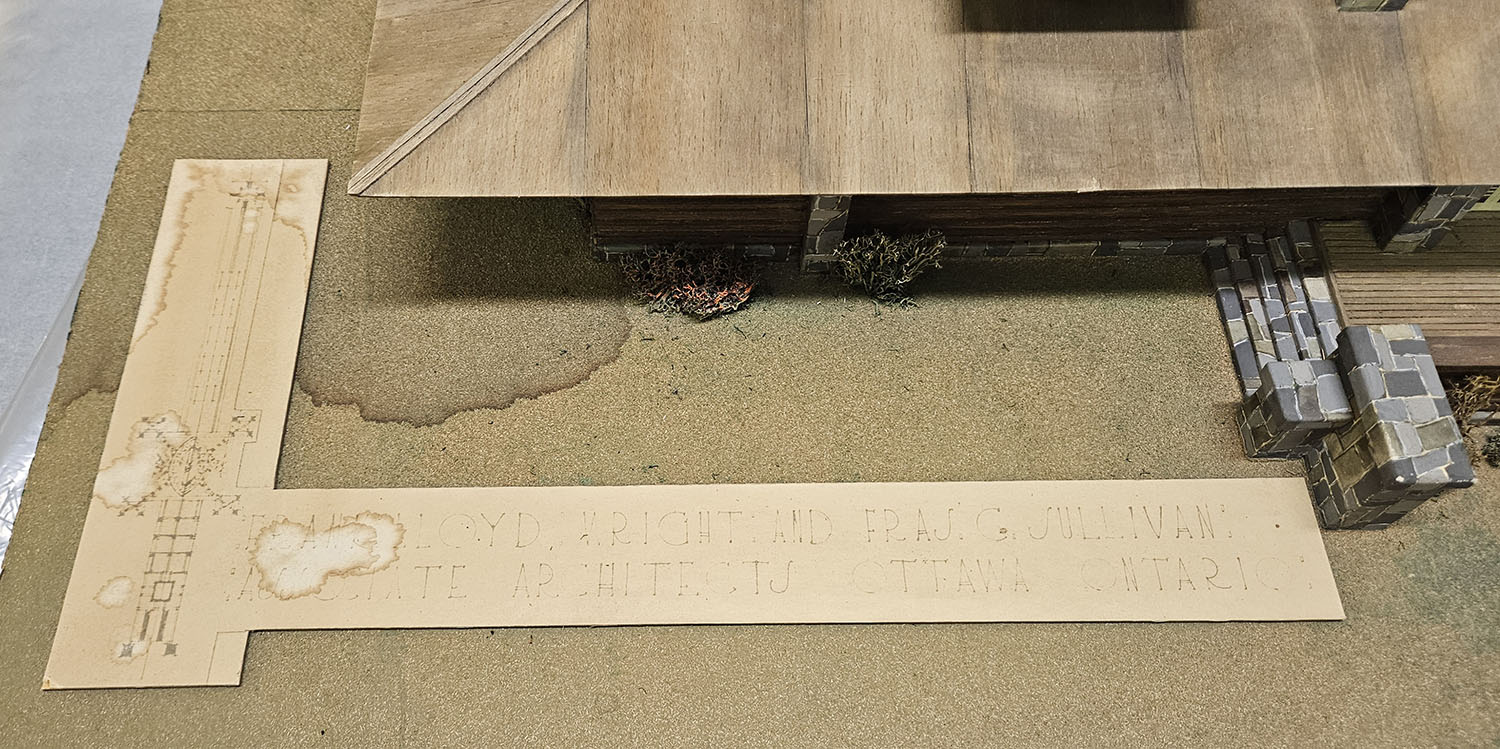

There once was a Frank Lloyd Wright – designed building here, in the midst of the splendor of the Canadian Rockies, in Banff, Alberta.

There once was a Frank Lloyd Wright – designed building here, in the midst of the splendor of the Canadian Rockies, in Banff, Alberta. Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion West Face – Image #V683/VI/A/PG-336 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections

Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion West Face – Image #V683/VI/A/PG-336 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections From the University of Calgary Digital Collection

From the University of Calgary Digital Collection

The River Forest Tennis Club in 2020

The River Forest Tennis Club in 2020 Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion Interior Image # V683/441/na66/1471 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections

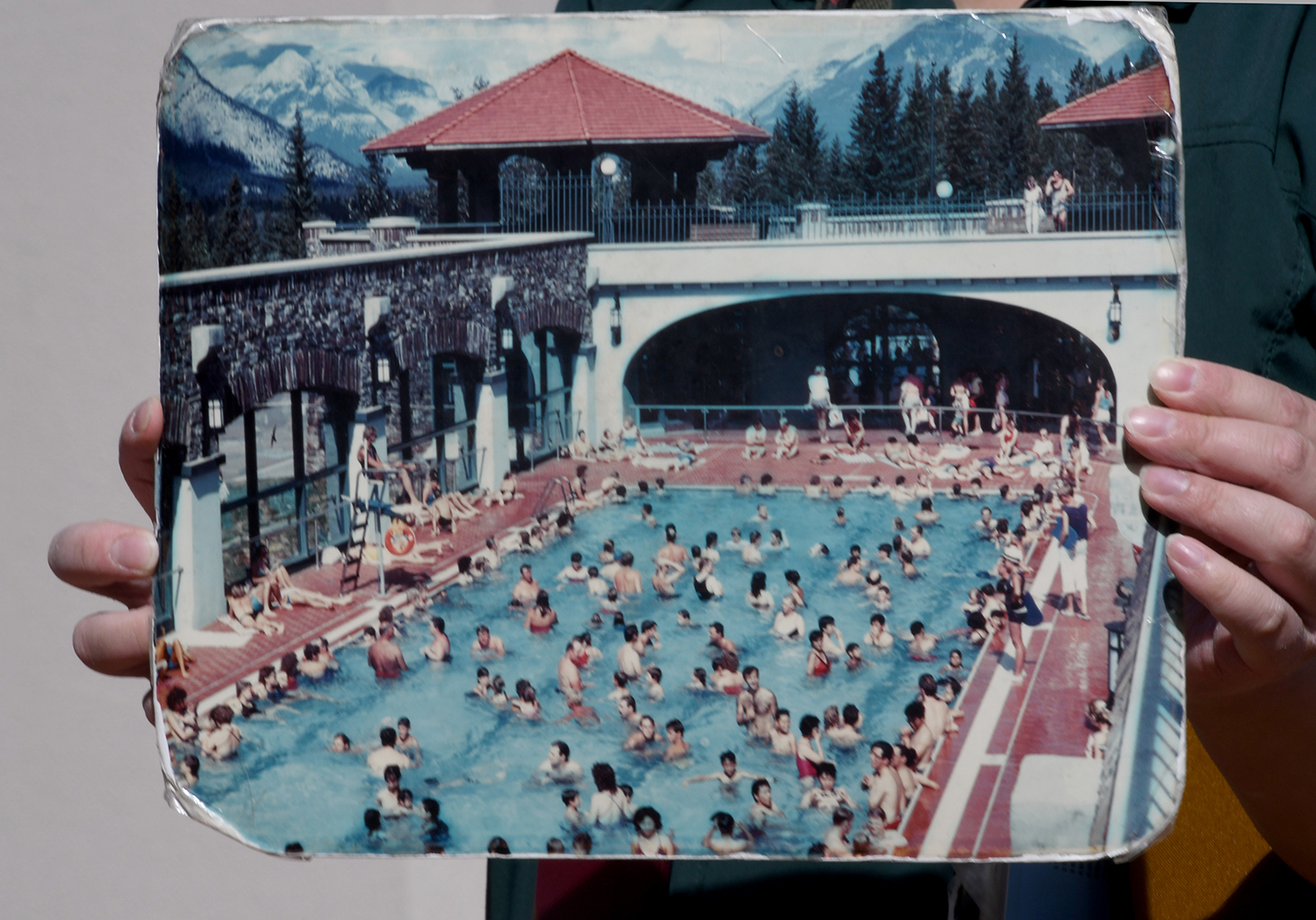

Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion Interior Image # V683/441/na66/1471 – The Whyte Archives & Special Collections From the University of Calgary Digital Collection

From the University of Calgary Digital Collection Patricia Thomson helps us locate the site of the Pavilion. Photo by Cindy Hertzberg

Patricia Thomson helps us locate the site of the Pavilion. Photo by Cindy Hertzberg

Images courtesy of The Whyte

Images courtesy of The Whyte Workers smooth out newly poured concrete at the entrance to the church Thursday June 19. This is part of Phase 2 of work at the church.

Workers smooth out newly poured concrete at the entrance to the church Thursday June 19. This is part of Phase 2 of work at the church.